Blog Posts

November 13, 2025The Situational Leadership Model

November 13, 2025The Situational Leadership ModelBy Dr. Scott.

Last week, we started a short series on Situational Leadership. In 6 Characteristics of Situational Leaders, we introduced situational leadership theory and explored some of the behaviors and best practices of effective situational leaders. In that piece, I also stated that it is best to think about situational leadership as a process and we’ll explore that concept in greater detail, albeit with some minor caveats which I discuss below.

As we examined in 6 Characteristics of Situational Leaders, situational leadership began with the work of Ken Blanchard and Paul Hersey back in the late 1960s. The theory, and the models that followed, focus on a leader’s need to alter their leadership style to align with a follower’s level of development, the complexity of the task, and the nuances of the situation.

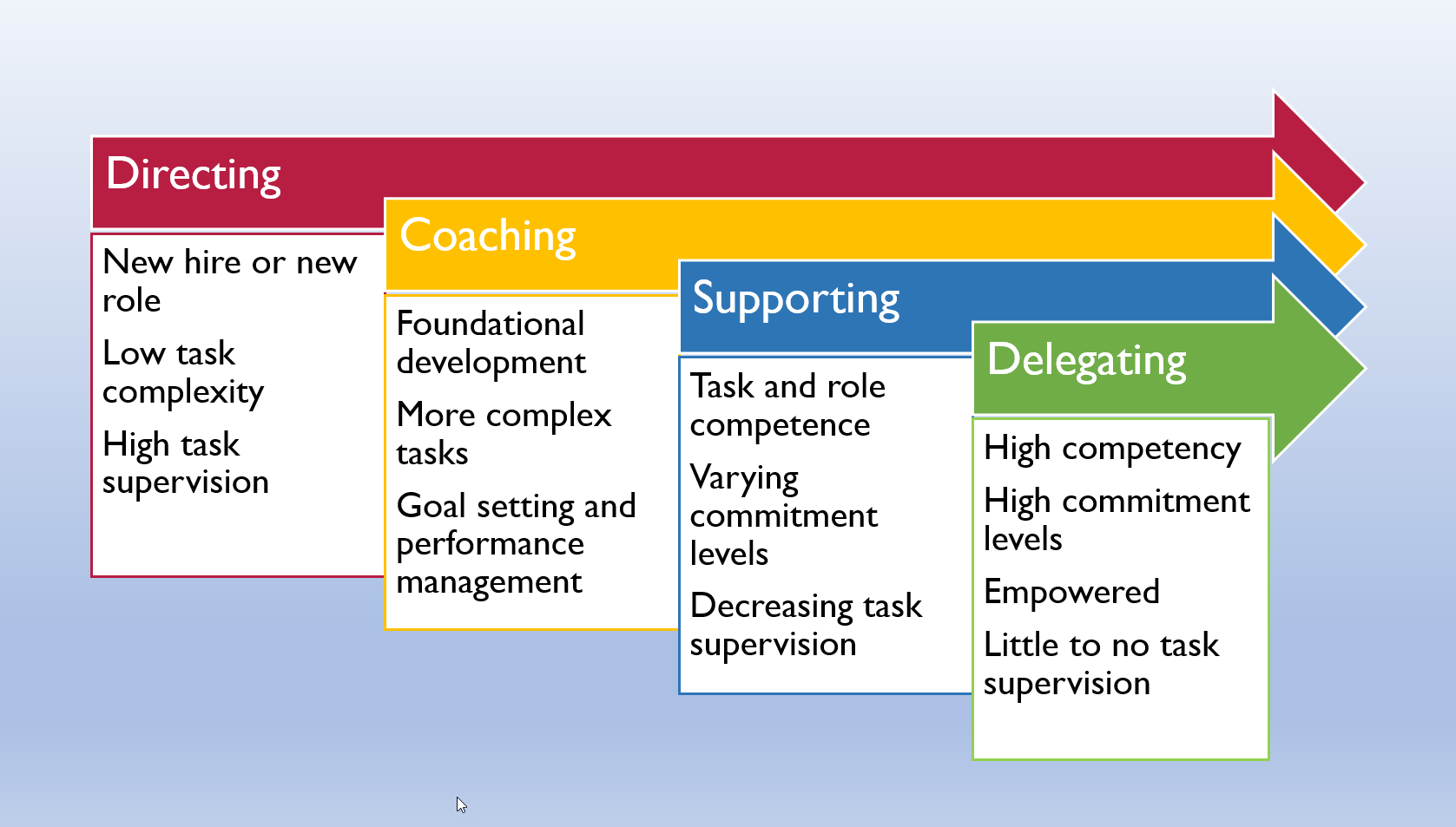

The model, though, is more than just a how-to guide for remaining flexible, adaptable, and open-minded. The model actually consists of four quadrants that represent four important stages. These stages are meant to guide leaders and their teams through the situational leadership model, with the end goal being well trained and highly skilled team members capable of working independently. Organizationally, the desired outcomes are strong, cohesive organizational cultures and high performing teams and divisions.

In this week’s installment, then, we’ll take a quick look at the four quadrants of the situational leadership model so that, in future installments, we can break down each phase and present some real-world applications. There are a few variations out there, but the quadrants we’ll discuss today are: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating.

I mentioned some caveats to thinking about situational leadership as a clear-cut process. Application of the model requires constant assessment of a team member’s task competency and commitment, which may fluctuate and even regress. Related to this, in the sections below, I will be describing each phase as part of a new hire’s trajectory through the model. However, I should stress that we are discussing a model that is meant to help us conceptualize the process, but that, in real life, pathways through the four stages will be no doubt vary for different individuals, unique situations, and shifting levels of commitment. I have therefore also included some examples of when each phase might be applied to situations where experienced team members may lose motivation or commitment.

Directing

The first phase is the directing phase. Another way to think about the directing phase is as the telling phase in that leaders tell followers what to do or how to do something. In this first phase of the Situational Leadership Model, leaders focus their efforts on training either a new hire or someone in a new role and establishing or improving task competency. In this context, by task competency, we mean the specific requirements for the job and the job description.

This new individual has very low task competency and requires a great deal of supervision. Leaders, therefore must spend the majority of their time and leadership efforts instructing the individual on task competency. Typically, in this stage the new team member is excited and has high levels of commitment, however, experienced situational leaders should also rely on a directing leadership style when attempting to motivate unmotivated or underperforming team members. A running constant throughout the directing phase of the Situational Leadership Model is a high task focus with low relationship focused behaviors.

Coaching

Once the new team member has mastered some of the basic tasks required for the job, situational leaders can then begin to shift their focus to relationship building and goal setting. In this coaching phase of the process, leaders are still focused on task competency and increasing the complexities of the tasks the individual is asked to complete, but the leader now includes high relationship focused behaviors. One reason for this is that, at this stage, the new team member often has decreasing commitment as they are being asked to take on more and more complex tasks and responsibilities. Therefore, reestablishing buy-in is key to this coaching phase. Goal setting, relationship building, and motivational best practices are key to successful graduation to the next phase in the Situational Leadership Model

Supporting

In the third phase, the individual has developed into an experienced team member. Their task competency is high as is their commitment. However, a supporting leadership style can also be applied when highly competent team members are waning in commitment or motivation.

In the supporting phase, situational leaders can begin to focus more and more of their attention away from a task focus and move on to some high relationship behaviors such as long-term goal setting, professional development, and empowerment.

Delegating

In the delegating phase, the team member has achieved high levels of competency and ownership of their tasks and role. At this stage, situational leaders engage less and less with task specific guidance and focus almost entirely on high relationship leadership behaviors such as encouraging ownership and buy-in and delegating responsibility and decision making.

Final Thoughts

In this article, we laid a foundation for some later explorations of situational leadership applications. Specifically, we examined the Situational Leadership Model. The model, first put forward by Ken Blanchard and Paul Hersey back in the late 1960s, presents four leadership style quadrants or stages in a leadership process: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating.

In our discussions here, I presented the model through the lens of a new hire, but the model is much more robust and situational leadership best practices should also be understood as assessment tools for a, more often than not, non-linear process. These tools serve as a framework that helps leaders establish a “where are we today?” style of leadership that, when applied correctly, is very effective in improving team member task competency and establishing buy-in, strong motivation, and high commitment.

In upcoming weeks, we’ll explore each quadrant in more detail and explore some real-world examples and applications.

Thank you for reading the Madison School of Professional Development Wednesday Leadership Blog where we highlight leadership best practices each week. Check out more from this blog and other blogs hosted by MEG here.

If you have a topic that you would like to see me pontificate on, drop me an email at info@meg-spd.com.

Dr. Scott Eidson is the Executive Vice President of the Madison School of Professional Development and holds doctoral degrees in both history and business. When not thinking about leadership, he’s usually thinking about surfing or old Volkswagens.

December 03, 2025Situational Leadership: Directing (with Examples)

December 03, 2025Situational Leadership: Directing (with Examples) December 04, 2025December 7 1941 0748 Hours

December 04, 2025December 7 1941 0748 Hours December 17, 2025MEG Partners with Quality Innovations

December 17, 2025MEG Partners with Quality Innovations